Studying UK Jewish entanglements with Israel from below

A greater focus on oral history would allow different narratives of British Jews' relationships with Israel/Palestine to emerge

This talk was first given at the International Oral History Conference in Krakow in September 2025, as part of a panel of Jewish and Yiddish academics, also featuring Tal Hever-Chybowski, Annabel Gottfried Cohen, Ben Rogaly and Samuel Solomon. It was repeated as an online webinar in January 2026 under the title Jewish and Yiddish Reactions to the Destruction of Gaza: a Panel, the recording of which has now be uploaded to Youtube. My talk begins around the 40 minute mark.

Despite the important role oral history has played in British history since the 1960s, it has played only a minor role in the writing of British Jewish history. The oral history work that has been done has been heavily based on refugee experience; particularly with Holocaust survivors; Jewish refugees from the 1930s and 1940s and projects on Kindertransport children and those who were given refuge after the Second World War. Much more recently the project Sephardi Voices has carried out interviews with Jews who emigrated from the Middle East, North Africa and India in the postwar era. The emphasis was usually on the refugees’ early lives in their country of birth and then on their migration experience, their later lives in Britain received much less focus. The are also some regional collections: the Manchester Jewish Museum has an important archive of 530 interviews with Mancunian Jews, and the Scottish Jewish Archive Centre holds 130 interviews with Scottish Jewish community members.

While not exactly oral history, there have also been some significant surveys. Notable examples include the Edgware survey, carried out in 1968-1969 by Ernest Krausz and the 1978 survey of Redbridge carried out by Barry Kosmin and Carey Levey, under the auspices of the Board of Deputies research unit.[1] These surveys were often most interested in changing Jewish demographics rather than the life experiences and views of those surveyed. Their primary aim was to help communal professionals understand where resources were most needed in terms of Jewish schools, retirement homes and synagogues. The questions asked were determined by the researchers rather than the priorities of interviewees.

That is the broad picture. What of British Jewish engagement with Israel? In the twentieth century Palestine and subsequently the State of Israel came to play an increasingly oversized role in the life of British Jews. But there has been very little oral history on this subject, neither on British Jews who chose to make Aliyah or those who stayed in Britain but whose Jewish identity became shaped by Zionism and Israel.[2] It is interesting to reflect on the reasons for this lacuna – perhaps because in the earlier period British Zionism was quite a limited phenomenon, epitomised by a small number of individuals and institutions who sought to influence the diaspora and induce them to express their Jewishness in more Zionist ways. Oral history would have revealed a less Zionist community than communal leaders and funders wished to admit so there was little impetus to engage in it.

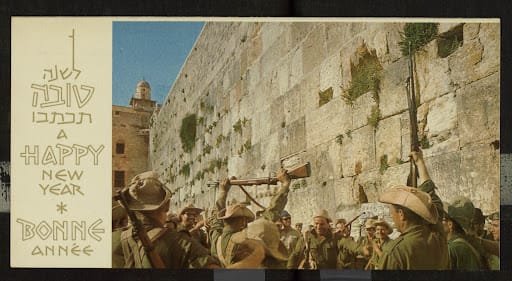

Changes in such communal attitudes in the late 1960s were the subject of doctoral research by Jamie Hakim.[3] Hakim conducted interviews with 12 British Jews who lived through the 1967 war, reflecting on their perceptions of it and how it shaped their Jewish identities. He noted that they experienced the run-up to the war as a period of tremendous fear; believing that a second Holocaust could occur should Nasser invade Israel (even though Israeli historians have shown that there was no such risk). Prominent British Jewish figures wrote letters in support of Israel in this period, including those like Ralph Miliband and Harold Pinter who would go on to be anti-Zionist critics of Israel. Because of these fears, the sense of elation at Israel’s rapid victory and territorial conquests was all the greater – they were experienced in religious, messianic terms, as if Jews had suddenly been redeemed from darkness into light. Hakim found that in describing this period his interviewees underwent bodily shifts – from a sense of constriction in describing the run up to the war to one of release and liberation when discussing Israel’s victory. He concludes, drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, that Anglo-Jewry underwent a physical change in this period, that the emotional outpouring changed the collective body of the Jews of Britain. Hakim’s research holds interesting lessons about researcher subjectivity; he was only able to gain access to his subjects because of his Jewish and Zionist background, and the corresponding assumptions the interviewees made about his political views. They assumed he would use the research broadly in support of Zionism; in fact, he drew on them to narrate an anti-Zionist account of the 1967 war and its impact on British Jewry. Hakim argued that 1967 created what he termed ‘popular Zionism’ amongst British Jews; a new form of identity expressed through social events, fundraising and tourism to Israel, made easier by the recent boom in air travel. It took an anti-Zionist scholar to both engage in such oral history and to name this phenomenon; to show that it was something new rather than an inevitable part of Jewish identity, as Zionists had maintained.

To add to such oral histories, I mine my own family experiences in ways which are anecdotal but perhaps illustrative. They all relate to the Hebrew language. My mother, born in Britain to Jewish parents in 1946, attended the Sunday morning religion school at the family’s local Liberal Synagogue. She remembered initially being taught Hebrew in the Ashkenazic pronunciation traditionally used in Western Europe. But then, at an unspecified moment, undoubtedly during the 1950s, she remembered being taught that everything had changed. From then on, they were to pronounce Hebrew according to Ivrit – the form of modern Hebrew used in the new State of Israel (In the recording I demonstrate this change through two melodies for the prayer 'Oseh Shalom', which have contrasting pronunciations). This was a huge change to how prayers were spoken; what could be a clearer encapsulation of way that Zionism was nationalising, or even perhaps colonising the Jewish diaspora? How did British Jews feel about this change to their ritual, surely on a par with the abolition of the Latin Mass under Vatican II? We don’t really know. Apart from my mother, nobody has really spoken about it, or at least nobody has been willing to listen. This is a piece of oral history research waiting to be done, while some of the people who went through it remain alive.

Fast forward a few decades, I attended the same religion school in the 1980s and early 1990s. We learned exclusively modern Hebrew, taught by Israeli teachers, who attempted to school us in conversational Ivrit, the language of the Israeli street rather than the siddur. The hope was that we would use it in the future on trips to Israel, and it once got me through the first 3 lines of a conversation on a Kibbutz. I remember a session where the Rabbi taught us chat up lines we might use on the beach in Tel Aviv, lines which I cannot remember and certainly never used. The policy was a clear statement of what the community thought Hebrew was for – for Israel rather than for the synagogue and the home. It didn’t work. We were terrible students, but I think one of the reasons the approach failed was that the everyday Hebrew of Israel was irrelevant to our lives. In fact, I don’t recall Israel being discussed much at all. The attempt to nationalise the diaspora, to turn the British Jewish community into a satellite of the Israeli state, had not fully succeeded. The only thing we were navigating was the familial and communal message that we were somehow different to other British people, when as far as we could ascertain, we were much the same. This shift to having Hebrew taught as a spoken language by Israeli teachers, also remains unstudied. I once spoke to a former religion school headteacher school and she suggested that the change had occurred after 1967, which feels plausible. Still there is so much we don’t know about how students responded to this policy, and whether the attempt to build a stronger connection to Israel worked any better in other places than it did in my synagogue.

The late 1960s does seem to have been a moment of transition. But I think we also need to appreciate that the era of hegemonic communal Zionism had an endpoint, or rather several points of decline. The first was the 1982 Lebanon war, particularly the Sabra and Shatila massacres for which Israel was indirectly responsible. This led to a wave of British Jewish protest and dissidence, most notably the establishment of a Peace Now group in the UK, in parallel to its creation in Israel.[4] The hegemonic consensus of popular Zionism began to break down in the wake of evidence of Israeli war crimes and the emergence of a strong anti-war movement in Israel itself. This breakdown continued in the late 1980s, with the outbreak of the first intifada in the West Bank and Gaza, a largely grassroots non-violent movement which the Israeli army put down with brutal force. In this period, the previous taboo on meetings with the PLO, the Palestine Liberation Organisation, began to dissipate in Britain, as figures as diverse as the Jewish Socialists’ Group, Board of Deputies senior representative June Jacobs and Liberal Rabbi David Goldberg all met with PLO representatives, in the face of opposition by communal leaders. There were a range of Jewish-Palestinian dialogue groups in Britain, both privately in the run up to the signing of the Oslo accords, and more publicly after it. It would be tremendously instructive to hear how Jewish participants were affected by such dialogue, but almost none of this has been studied as part of oral history.[5]

Following this 1980s shift, the Oslo peace process saw a new era of British Jewish attitudes towards Israel, as the work of the Israeli New Historians became known in Britian, and Palestinians became less feared. This change was one factor which contributed to a tremendous optimism and creativity amongst British Jews in the 1990s and early 2000s.[6] Following 9/11, the 2005 terrorist attacks and a series of wars between Israel and Hamas from 2007 onwards, attitudes hardened once again, and views on Israel returned closer to how they had been in their 1967-1982 heyday. But it was not the same; popular Zionism had broken down, and younger generations, especially those who came of age after 2001 had not inherited the instinctive fears of annihilation and feelings of redemption that those who remembered the events of the late 1960s and 1970s had undergone. Once again, these voices have not been heard in oral history research, but Robert Cohen recently completed a doctoral thesis based on interviews on journeys towards Palestinian solidarity amongst British Jews in their 20s and 30s; precisely the generation that I am discussing here.[7]

In the place of oral history, one alternative way that British Jewish experiences have been recorded are through antisemitism statistics. Since 1994 British Jews have been able to submit their experiences to the Community Security Trust, CST; so long as those experiences can be understood under the category of antisemitism. But their voices are barely recorded in the reports that CST creates. Most reports are collated to give total figures for each of the CST’s categories of antisemitic incidents, so the submissions simply become source material for statistics. A few voices are quoted, but those chosen tend to be the ones that have had the worst and most shocking experiences. The voices of those who were not too upset by their experiences, or who did not experience any antisemitism at all, are absent from these reports. This is relevant in understanding the history of British Jewish attitudes to Israel because sometimes anti-Israel protests have been collated as antisemitic incidents and anti-antisemitism work is often Israel advocacy by other means.

The other major way British-Jewish voices are heard is through surveys carried out by the charity Jewish Policy Research, JPR, which began conducting these around the millennium. The questions are set by JPR, limiting their value as oral history, and once again the primary aim is to create statistics: how many Jews engage in key observances, how much to do they participate in the community, and so on. In the last decade the surveys have focussed more on attachment to Israel and to its political decisions, a trend which has increased since October 7 2023. They have picked up a significant decrease in the number of British Jews identifying as Zionists and an increase in the number opposing Israel’s policies in Gaza and the West Bank. Were there to be significant uncontrolled interviews conducted amongst British Jews today it is likely they would show that ‘Popular Zionism’ has largely broken down, that the centre has been unable to hold and that British Jews are increasingly polarised between a non- or anti-Zionist left and a Kahanist right. It is thus unsurprising that no communal organisation has been in a hurry to commission such research.

Towards the end of this year’s survey JPR asked a group of questions about feelings: Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?; overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?; and overall, how happy did you feel yesterday? I have no idea what JPR hopes to do with these answers. I can only speculate that they are expecting a high degree of negativity in response to them, which can then be presented as Jewish trauma in the wake of October 7th and the apparent rise of antisemitism since then. Jewish diaspora emotions are relevant, but only when they can be utilised to support certain narratives around antisemitism and Israel, even better if they can be used as evidence by the British state to crack down on protest and non-violent direct action.

So where does all this leave us? It shows that the relative absence of oral histories of British Jews’ approach to Israel is political; borne of a communal unwillingness to show how new and different the popular Zionism movement of the 1960s was, and how much disintegration and change has occurred since then. It is in the interests of those who think things can be otherwise – that Zionism and support for Israel does not emerge organically from Jewish identity but must be constantly produced and reproduced - to engage in more such oral history, to amplify the voices of ordinary British Jews and show how they have navigated this complex terrain. We need a British-Jewish history from below; to interrogate the ways in which Zionism colonised the British Jewish community as well as colonising historic Palestine.

[1] Ernest Krausz, Jews in a London Suburb: The Edgeware Survey (London: World Jewish Congress, 1970); Barry Kosmin and Carey Levey, Jewish Identity in an Anglo-Jewish Community: The Findings of the 1978 Redbridge Jewish Survey (London: Board of Deputies, 1978).

[2] A chapter on British olim in Gavin Schaffer’s An Unorthodox History: British Jews Since 1945 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2025) is a rare and recent exception to this rule.

[3] Jamie Hakim, Affect and Cultural Change: The Rise of Popular Zionism in the British Jewish Community After the Six-Day War, PhD Thesis, University of East London, 2012.

[4] See Jack Omer-Jackaman, The Impact of Zionism and Israel on Anglo-Jewry’s Identity, 1948-1982 (London, Vallentine Mitchell, 2019. See also Imogen Resnick, The Forgotten Rupture: Lebanon ‘82, Anglo-Jewry and the British Political Left, unpublished undergraduate thesis, University College London, 2018.

[5] See Imogen Resnick, Diaspora Jewish-Palestinian Relations and Israel, 1986-1996, unpublished Masters thesis, University of Oxford, 2019.

[6] The work of memoirists like Victor Seidel and Ann Karpf, as well as New Moon magazine are testaments to this shift.

[7] Robert Cohen, Beyond Binaries: Journeys to Palestinian Solidarity among UK Gen-Z-Jews. A Study into their Backgrounds and Motivations, unpublished doctoral thesis, Kings College London, 2025.